AN old ute pulls up on Sea Lake’s main street swinging over to the curb and rolling into the shadows of a weathered, but still grand old dame.

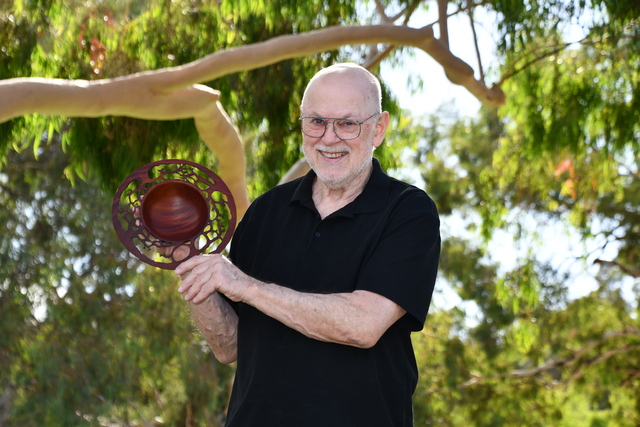

John Clohesy wipes the smell of stinking sheep from his nostrils and steps out onto the footpath to stand beneath her.

As imposing as she is, she’s tired and her walls are crumbling.

Old bits of mortar have tumbled from the second storey and lay scattered about his feet. John looks up to the warped balcony above as a pigeon flies through the broken glass of a top floor window. From street level, he peers inside and sees what was the heartbeat of his hometown now barely managing a pulse.

Through the bar door, John watches as the pigeon completes its journey down through the pub to its landing spot on the old bar. It shits where it sits, the brown and white stain dripping down the front of the bar symbolic of what this place has become.

Poor management and hard times were what closed the doors of the Royal Hotel, and as the key turned in the lock, it snuffed out the last breath of community spirit left in here.

John knew he had to do something. He’d been hearing on the grapevine that young families were packing their bags, ready to leave.

The town was struggling, and who could blame those wanting to cut and run? John rings his mate Andrew McClelland and together with Andrew’s builder brother-in-law, they force the door open. What they find inside is a dame who’s been deserted and her grandeur is fading to wreck and ruin.

The men trudge into what was the public bar, kicking empty beer cans away to reveal the old jarrah floorboards stretching across the room.

These were laid with pride 130 years ago. It was a time when the railway was first arriving in the wheatbelt town and weary farmers were thirsty for respite.

The old dame heaved then and for many decades after, but on this day in 2017, the only bar flies left are vermin. As John and his mates make their way inside, disgruntled pigeons flee their perch like old drunks on marching orders. The flapping of their wings disturbing a stack of yellowing papers discarded on the bench. They’re utility bills the former publican has left behind. John has a glance and shakes his head.

He follows Andrew through to the kitchen. The men peer inside to find a raw t-bone steak sitting on the counter, ready to be cooked. It’s as though the chef had just gone for a cigarette and never come back.

The stench of the room is overpowering and the men cover their noses in disgust. The cool room is still stacked with food and has been left to rot.

“It looked like a murder had gone on there and everyone had just bolted,” says John.

John has seen enough and goes home to his wife with a pledge.

“I’m going to buy this place,” he tells her.

His comment is met with raised eyebrows and a “no, you are not”.

John is on a mission, though, and word quickly spreads through the town. At the footy, his mate David Mortimer offers to pitch in with a cash contribution as do many others around town who’d also been watching the old girl in the main street gasping for air.

Before John knows it, he’s making himself welcome at the hotel again, bringing with him a prospective investor who had a family connection to Sea Lake and penchant for the finer things in life.

The Geelong man takes one look at the exposed brick on the walls and says to John, “ are we going to plaster over those bare bricks? it’s a sign of poverty you know.”

John scoffs back: “No way in the bloody world.”

Despite their differences on interior design, John still manages to secure a significant investment from the gentleman and the Royal Hotel Co-Operative is well on its way to formation.

By the time the pub went up for auction in November 2018, 42 investors were behind the co-op, and such was the desperation to resuscitate the hotel, even teetotallers were throwing money in. Local woman Laurice McClelland was one of them.

“She loves the community that much that she invested,” says John.

Once they’d secured the sale for $180,000, John says, “the phone just would not stop ringing, people wanted to be a part of it.”

So from then on, John tells me, the town would pile into the old pub every Tuesday afternoon to brainstorm its rebirth.

“The only condition was you had to bring our own chair and a slab,” he says.

“It was fantastic. People would just walk in off the street and offer their ideas.”

He remembers the day he was working on the old balcony and a young man he didn’t recognise asked what he was doing.

Turns out it was champion road bike racer Reece Payne, who also happened to also be a cabinet maker. He promised John: “I’ll build you the best bar in Australia,” and John says he did. It’s the passion of people like that meant more than the bricks and mortar they were working on, and there was no one more dedicated to the task than old Tom Elliot, from the local Men’s Shed.

Tom wasn’t a shareholder in the hotel, but walked in one day and noticed the original jarrah floor boards that had been ripped up to form part of the new bar were coated in sticky old linoleum glue. The 80-year-old quietly took the wood away and doggedly sanded every spec of glue off the boards.

“He did it all by himself,” says John.

“He didn’t trust anyone else to do it. He was at it for weeks and weeks and weeks. The Men’s Shed power bill shot up to $700 so we paid it for him.”

When a working bee was called, 80 people arrived with their sleeves rolled up.

They helped drag away mountains of filthy old mattresses and 28 truckloads of rubbish.

Meanwhile, John was pulling together a board of directors for the co-op. He knew there were some clever minds in town because only a couple of years earlier they’d banded together to save the town’s hardware store.

So, John says, “I picked the best five people I could find and I didn’t ask them to be involved, I told them.”

One of those people was Alison McClelland, who John says works tirelessly behind the scenes as the hotel secretary.

“If it wasn’t for her, some things just would not get done.”

According to John, the first six months of business absolutely boomed.

“There were nights where there were 150 people in the bar and not one of them were local.”

When COVID hit, they had to quickly pivot to takeaway and used the time to renovate the upstairs accommodation. The co-op managed to survive and when lockdowns were lifted, business returned.

“We were lucky enough that people from Geelong and Ballarat started travelling again,” John says.

These days, alongside tourists at the bar you’ll often find a local farmer enjoying a beer that little bit more than his neighbour, especially at harvest time.

There’s pride in the fact that the barley they grow just down the road does a round trip to Carlton United Brewery in Melbourne, and ends up back in Sea Lake in a beer glass in front of them.

There’d be no toast to them though, or the town itself, if it wasn’t for that group of people who saw past the broken bones of this grand old dame and put their hands on her heart instead, pumping like crazy until she drew breath again. That effort didn’t just revive a pub, but an entire town.

According to John, “we never imagined it would do what it did. We just wanted to have a beer.”