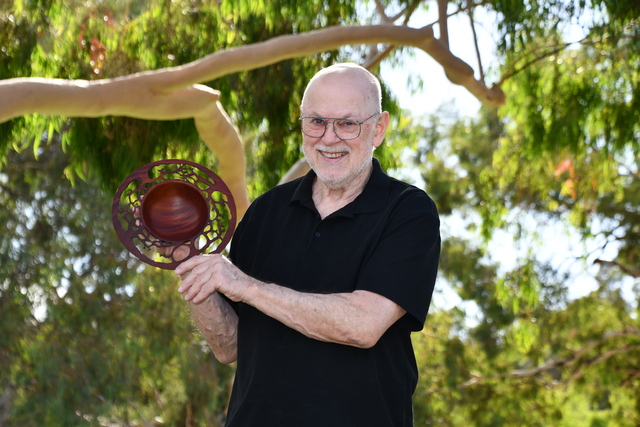

FOR Swan Hill artist Glenda Nicholls, grass-basket weaving is a way to continue a long family storyline.

The proud First Nations woman is part of the art collective Ngardang Girri Kalat Mimini, which translates to “Mother Aunty Sister Daughter”.

Earlier this month the collective unveiled their latest work, entitled Creative Resilience, a 4.6-metre sculpture that stands outside the Queen Victoria Women’s Centre.

The sculpture portrays the arm of a First Nations woman, proudly displaying a woven grass basket on her flat palm.

Nicholls says the sculpture is a celebration of the creative endeavours of past, present and future First Nations women.

“It’s all about people like our matriarchs,” she said. “Who have handed down these arts and crafts to the rest of us.”

“It’s for the ancestral mothers of the past, the ones who are still here in the present and also the ones of the future.

“People like my mum, Letty Nicholls , who was brought by her grandparents across the country to Swan Hill.”

“That hand represents all of our hands and is something that belongs to all of our First Nations women.”

The large, copper-dipped basket atop the sculpture began as a 10cm grass basket, woven by each of the six members of NGKM.

Each member used native grass to complete the basket, before it was moulded and transformed into the larger basket. One of the artist’s arms was also moulded to create the lower portion.

Nicholls said planning was important to ensure all First Nations cultures were represented.

“We had a lot of discussion,” she said. “And I had a great time working with the team.

“Having those discussions about how we could make something that represented all First Nations women was really important.

The sculpture also features a QR code that will lead viewers to hear stories from its artists.

The sculpture isn’t just about its beauty for Nicholls, who sees it as an important learning tool for all.

“There is a whole history of First Nations women doing arts and craft,” she said. “But that was always kept behind the scenes, because it was a man’s world.

“I also feel like First Nations work has been exploited a bit. When we go out to teach a workshop, we want to teach people the art while also telling the story of where it came from.

“Sometimes it can feel like people only care about learning the skill and passing that on, while completely forgetting to tell the story behind it as well.”