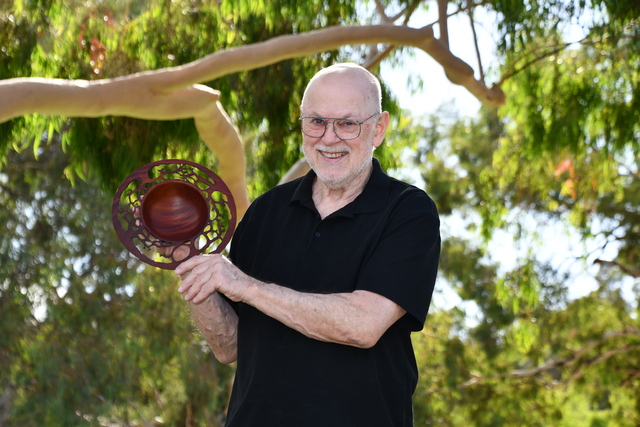

IT took 31 years and heat stroke to make 85-year-old Bill emerge from his Nyah Forest home and begin re-entering society in February.

A plastic bag tied to a tree with a note was the first communication Bill initiated since he drove his Nissan Patrol into the forest in 1994 and built a shack around it.

“All the tucker was there and it was quite good,” he recollected of his arrival to the forest.

“The rest is history – until I got crook.”

Although in the decades past Bill had weathered up to 46-degree heat, digging himself a cellar under his shack to stay cool, he fell ill in February with severe heat stroke that effected his hearing and gave him hallucinations.

Knowing he would not survive much longer without medical treatment, Bill traversed the 100-yards of bush scrub and his own obstacles to implement the SOS he had devised with Swan Hill Police years before.

“I need food and medical treatment. Please contact Brian at Swan Hill Police Station as I need some advice for the future,” his note read in an elegant script on a scrap of cardboard.

Sergeant Brian ‘Mouse’ Molloy and Wangaratta Senior Sergeant Michael ‘Mick’ Mannix, formerly of Nyah, have minded Bill’s welfare since 1996, making regular visits and becoming friends with him through the years.

“He’s the most sane guy I know,” Sen-Sgt Mannix said.

“I had heard some rumours about Bill around Nyah, but when I met him he was mentally and physically fit, intelligent, well-read and had made a choice to live his life in the forest.

“He was totally conversant to what was going on – he would comment on my footy season when I visited and was up to date with current affairs, he read the newspaper every day and had his radio, and has a huge library.

“I offered support and welfare, he knew he could ask me if he needed assistance, and I knew he could manage his own welfare.

“I respected his wishes from the start, and I would consider us best mates now.”

When Sen-Sgt Mannix transferred to Wangaratta, he briefed Sgt Molloy on Bill’s situation and tasked him with the regular welfare checks.

“I had to find someone to continue providing care with that attitude of respect for his wishes, and that was Mouse,” Sen-Sgt Mannix said.

It took Bill two years to come out of his shack during Sgt Molloy’s visits, but they developed a friendship that saved his life.

“He would always smile and laugh when I would tell him he could come out and we could help him set up a pension; I knew it was never my place to question him or move him on,” Sgt Molloy said.

“Every time I saw him I’d see he wasn’t in as good nick as the last time, but we had the system set up so I knew he was able to ask me for help if he needed it.

“Mick and I knew and accepted that we would eventually go out there to check on him and he would be gone.

“I saw him about two weeks before we got the call, and when I saw him again I didn’t like the look of him – I wasn’t sure if he would make it.”

When Bill returned to his shack from tying the note and plastic bag to the tree on the trailside, he bunkered down in his cellar and waited.

“Are you there, mate?” he remembered hearing after an indeterminate amount of time.

The effect of heatstroke on his hearing meant he could not tell whether he had really heard the question, nor which direction it may have come from.

“I had a bit of a stroke, I think, and lost my hearing,” he said.

“I heard a magpie and I had no idea where it was coming from because my right ear was giving me trouble.

“I heard a car on the highway but there was no betting which way it was coming from.”

When Sgt Molloy and First Constable Dylan Roberts found Bill in the cellar and asked if he could climb out, Bill replied “I don’t know about that.”

“They got me up – I’d had a hard day,” he recalled.

“I grabbed a bit of wood off a tree and walked to the ambulance – it was a couple hundred yards and I didn’t think I would get there, but I’m still here.”

Since his visit to the Swan Hill District Health emergency department and admission to the acute ward, Bill has spent the last three months recovering from his ordeal and preparing for life outside of Nyah Forest with the tireless help of SHDH staff.

SHDH social worker Dr Cynthia Holland relied on her experience as a criminal barrister to wrestle the system to recognise Bill as a citizen so he could open a bank account.

“It’s amazing how someone can drop out of the system,” she said.

“It was a lot of work but somehow, we had to get through everything to set up a bank account and get him access to his pension, so it was about pushing everything as far as it could go to get a yes.

“Bill has not existed legally for 31 years, so I tracked down the record of him getting off the boat from Scotland as a Ten Pound Pom in 1961 to prove the law.

“As a social worker I had to move beyond ‘how are you feeling’ and get to the facts, that’s what banks and doctors care about.”

Bill said he couldn’t thank Dr Holland enough for her support, crediting her for his ability to move back into society.

“If I touched that thing (gesturing to Cynthia’s smartphone) for two minutes I would have ruined it, but she has got her fingers working all the time tapping,” he said.

“I would have given up trying to get everything sorted without Cynthia.”

Sgt Molloy echoed the sentiment, admitting that he panicked at the thought of how Bill would be treated in the system.

“I was worried people would try to act with the best of intent but end up going against Bill’s interests, but Cynthia totally understands him and respects his rights as a free man,” he said.

In his time making friends with every SHDH staff member he came in contact with, Bill’s story has become clearer.

He boarded the ship Canberra in Southampton, Britain on June 2, 1961 to start anew in Australia, having known someone else who had made the move.

“Knowing someone here was the biggest reason I went – it’s a lot of help, knowing someone already and having somewhere to stay for a couple of weeks,” he said.

“The boat over was an amazing voyage.

“The Canberra was brand-spanking-new and had air conditioning, which was good because when we went through the Red Sea it was 120 degrees [Fahrenheit].

“That ship ended up taking folks down to the Falklands War.”

His apprenticeship as a butcher in Scotland helped him find secure work.

“I worked in 40-degree heat with no water in Warracknabeal for about six months, and between Christmas and New Year, 1961, I went to Avoca to work as a butcher until, I think, 1968,” he said.

“Then I got a job in the council doing building and concreting work until I got sick of it – I can’t go through life doing the same thing.”

From Avoca, he went to pick fruit in the Mornington Peninsula for five years, and then in Robinvale for about six months.

“I still had a house in Avoca that I went back to, but I ended up back at Nyah,” he said.

“I had my 4WD car, some camping gear, a fridge, a camp cooker, a bed, a sink.

“I built a wood fire from a 44-gallon drum – I found a hacksaw and cut it to shape, made a base and surrounded it with corrugated iron to stop the sparks.”

While Bill effectively quit participating in the world outside, he did not quit working, holding noxious weeds at bay and tidying up years’ worth of rubbish.

“I thought I might get away with [living there] if I worked and tidied up,” he said.

“I used to cart half a ute load of rubbish to the tip every night – all sorts of rubbish that people had dumped there over the years.

“I found bits of cars, tar pots, lots of stuff.”

Bill’s ingenuity kept him busy and alive, pulling together the odds and ends he found in the rubbish to meet his needs.

“Bill’s quite a genius,” Sen-Sgt Mannix said.

“He made a lock for his back door with window winders from the insides of car doors, and that beat us for a while.

“He grew a garden and fruit trees, his insulation was a wall of 10L drums, he found solar lights he could use to read at night, he adapted chargers for all kinds of batteries, and he dug the cellar to keep cool in summer because it stays about 16 degrees underground.”

Before the solar lights, Bill used candles and fuel to read at night.

“I tried to make my own wax from sheep skin by melting it down, but it didn’t work – they wouldn’t last,” he said.

“I used birthday candles because people throw them out after using them on a cake.

“Kerosene heaters usually had a little bit of fuel left, or if there was a helicopter job on the Murray I would take the kerosene they would leave behind, and I would manage to get a gallon or so of fuel.”

Helicopters are required to refuel from sealed drums to reduce the risk of the fuel becoming contaminated, so anything left in the drum was waste – Bill did not have to worry about contaminated kerosene.

Bill returned to his shack this week to collect his personal effects, including an extensive library and his diaries, and the police and Parks Victoria are now working to dismantle the structure.

“I have a lot of good books – there’s one on the Antarctic, full of penguins and things you wouldn’t believe; Robyn Davidson who went across Australia on a camel – those adventures are always good; the true story of Victorian cop Charlie Bezzina’s life; a history of Australia spanning from James Cook to the convicts to present day,” he said.

“I’ve been all over Australia but my biggest regret was that I never went to the NT.

“I have a lot of books from there by women from cattle stations, who do rodeos, all that sort of thing.”

While Bill was well aware of the world beyond Nyah Forest, the reality of interacting with modern technology was an experience for himself and Sgt Molloy.

“It was jarring when we were in the ED waiting room and he pointed to the TV and said he hadn’t seen one this century,” Sgt Molloy said.

“He felt sick in the car because he hadn’t travelled at 100km/h in 31 years.”

Now that Bill is recovered and has a valid ID and Medicare card, his pension and is fitted out with a new wardrobe, he is moving onto his next adventure.

“I have wide windows, a room with a view, and everything is contained in my room with my own air conditioner and bathroom,” he said of his new home.

“The noise in the hospital bothers me a lot, I’m not used to it, and I struggled sleeping and eating in my first weeks here.

“I get to have privacy and be independent again.”

For Sen-Sgt Mannix and Sgt Molloy, Bill’s transition into his retirement from forest life has gone as well as it could have, considering the circumstances.

“From our point of view, he got to live the life he wanted for as long as he was able; we were happy to go out there and happy for him, and now we’re proud of him for asking for help when he needed it,” Sen-Sgt Mannix said.

“These are such unique circumstances that I have never seen before and I will never see again in my life, and we’re absolutely rapt with how this has turned out.

“He’s so excited for what’s next.”

While it may be hard for some to understand Bill’s motivation to live as a recluse in the Australian bush for 31 years, for Bill it is simple.

“I went into the bush every chance I got,” he said.

“I like being alone, I’m good in my own company and that’s the bit most people can’t understand

“I was born to be free.”

The SHDH executive team wished Bill all the very best in his future.

“We are incredibly proud of everyone directly involved in Bill’s care, and equally grateful for the many staff members whose everyday efforts make a real difference to our patients,” they said.

“In a hospital, every role is that of a caregiver.

“It’s through this shared commitment that we’re able to provide the level of compassionate support on display here.”

Sen-Sgt Mannix and Sgt Molloy request that the community respect Bill’s privacy and allow him to interact with people on his own terms to aid in his adjustment.