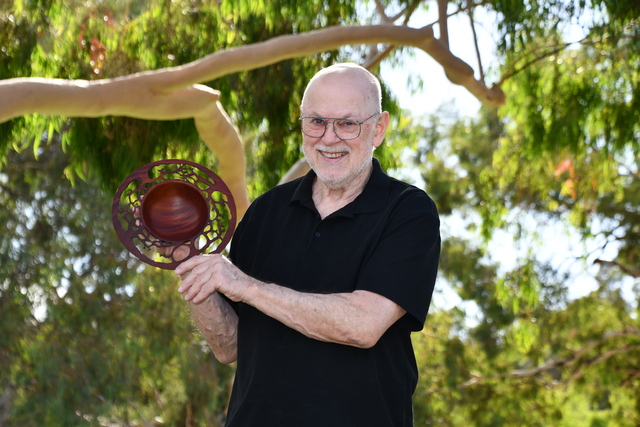

AFTER two decades battling a decline in kidney function, an organ transplant has given Swan Hill’s Keven Bowen a far brighter future.

Diagnosed with IgA nephropathy — an immune system issue that attacks the kidneys, causing inflammation and eventually causing them to shut down — around 20 years ago, Mr Bowen was placed on the waiting list for organ donation in late 2017.

With the backlog of recipients putting the waiting period between three to five years and doctors advising Mr Bowen dialysis would only work for another three at most, it was a difficult period.

Until his sister, Vikki Cane, stepped up and offered to donate one of her kidneys.

Nearly three months on from the operation, Mr Bowen told The Guardian he feels incredible, having received the greatest gift of all: quality of life.

“I feel great, and I have felt well,” he said.

“Obviously I have felt tired, I fatigue easily, because after having been diagnosed 20 years ago I have been on light duties for that entire period.

“So you have a lot of muscle wastage that is going to have to be rebuilt, so I’m taking walks in the morning and I’ll probably start gym to see if I can improve my upper body strength as well.

These seem like simple things, but prior to the operation they were impossibilities.

“You have no idea, it is sensational just to have the freedom to even think about these things,” he said.

“There’s a bit of spontaneity to your life that didn’t exist before, you were tied to a routine.

“Up in the morning early to finish dialysis, and then work through the day as normal as you possibly could, knowing that at 4pm your day stopped and you started dialysis again to prepare for the next day.”

With around five per cent kidney function, it was an isolating routine Mr Bowen could not afford to drop, and he admits the dialysis had begun to wear on him towards the end.

“Even though I was feeling well while I was doing it, that routine really wore on you,” he said.

“Psychologically, I was getting towards the end of being able to do the dialysis, I really struggled in the last few months.”

Mr Bowen said he was unsure if it was the promise of a transplant that increased his frustration, or simply the intensive process, but either way it left him in a dark place.

However, as bleak as things seemed, Vikki’s gift provided the hope of a better future.

Mr Bowen had already turned down similar offers from his daughter, nephews and nieces, not wanting to negatively impact their lives at such a young age.

But with Vikki persistent and well-informed of the risks, and Mr Bowen struggling with the intensive regime of peritoneal dialysis, he accepted.

Despite an early setback where doctors declared Vikki an unsuitable donor, eventually reconsidering due to a lack of other options, Mr Bowen said it was full steam ahead from there.

“We had the operation on August 29 at the Austin Hospital…and from there it just gets amazing,” he said.

“Vikki goes in at 8am, they remove her kidney, so I know she is out of theatre and safe before I go in.

“That was always my biggest fear, that I receive a kidney and she has compromised her life, I don’t know how I would have handled that.

“So that was a huge relief before I went in, knowing that she was well.”

Mr Bowen went into the operating theatre at 12 noon, came out at 4pm and said he “felt great, even at that point”.

“I don’t know if it was just the fact it was over, obviously we had pains, but I felt bright,” he said.

“My wife commented I looked exactly the same coming out as I did going in, talking to the nurses as they rolled me down, being able to talk to her and my brother-in-law waiting for us in the ward.

“It was quite phenomenal and almost from day one I felt so much better.”

Mr Bowen said while there was the obvious physical improvement as the kidney started to work, he also noted a shift in his overall outlook.

“There was also the mental aspect of it, knowing that this is a journey we started 20 years ago, and we finally reached the point where it is starting to take place, and some positives have been built in along the way,” he said.

Vikki was up and walking from the day after the operation, and was out of hospital in three days.

Mr Bowen said despite some early lethargy as her body adapted, she was now back to where she was before, “walking 10 kilometers and looking at marathons”.

For Mr Bowen, the process was a little slower.

Out of hospital in five days, daily consults, and ongoing monitoring to monitor for signs of rejection.

While these appointments will eventually stretch out to six monthly checks, the 64-year-old will remain tied to the medical system for the rest of his life.

It is a vast improvement on his prior situation.

And while Mr Bowen admits the risk of rejection remains in the back of his mind, at the front is plans for the future.

These include a holiday with his wife and a camping trip with his brothers.

“I have twin brothers and they usually go off by themselves in March, April or May, when the weather starts to cool down, this time they might have a third member coming along,” he said.

Mr Bowen said he has grown closer to his family throughout his ordeal, with one twin Malcolm an attempted donor, and the other, Brian, having a son who had already had a transplant.

A more immediate bonus of the successful transplant has been the lifting of the restrictive diet Mr Bowen has been on for 20 years.

Once limited to a litre-and-a-half maximum fluid intake a day and unable to consume countless dishes, Mr Bowen said his diet now mirrors that of a pregnant woman; no soft cheeses, cured meats and meals are to be “either very hot or very cold”.

“When we left the hospital, we were staying in accommodation near St Vincent’s, which is a stones throw from Lygon Street,” Mr Bowen said.

“Now my first meal was at Toto’s Pizza House, I had pizza — no salami, because that’s a no no — and the first mouthful, you have no idea.

“If you have an extended period — and again we’re talking 20 years — watching this, you can’t have that, to have something like that, which was forbidden in the past, the flavour exploded in my mouth.

“I just can’t relate how good it was.”

Mr Bowen said it was “simple things that you notice the most”.

“Breaking that routine that I have lived with for so long, knowing that the future is a lot brighter from what it was in the past, you can look forward to things,” he said.

“In the past, if I was to travel I’d have to prearrange for chemicals to be there and I was carting a suitcase full of equipment with me, and that was without worrying about clothes.”

Mr Bowen said the restrictions had made it “impractical” to do anything outside of the house. “But now I travel with a backpack, it’s simple,” he said.

“They’re little things to the average person, they sit there and go ‘what’s the fuss?’ but when you walk out the door with a suitcase full of equipment, you go ‘I hope I haven’t forgotten anything, because you know it would be a disaster getting to the other end and finding an important piece of equipment has been left behind or the drugs haven’t arrived.

“Sitting there is this apprehension about everything you do.

“But now it’s socks and undies and off we go, it’s great.”

Mr Bowen said while he was still making weekly Melbourne trips for consults, it was now an enjoyable experience.

He also had nothing but praise for the medical system.

“I hear people complain about our medical system, but really it is quite sensational,” he said.

Mr Bowen said from one on one care to specialist treatment, medical staff went out of their way to keep him informed and out of danger from pre-op to post-op.

“When you have daily appointments you are reassured by being there that if anything happens they can fix it, but when they go ‘Okay, now you can go home’, there is an apprehension there when you go ‘Oh, really’,” he said.

“You think the support us going to drop off, but it doesn’t.”

Mr Bowen is the second successful transplant recipient in his family, and he can’t describe how much thankful he is to both donors.

“My nephew is now in his fourth year (since the transplant), he’s going well and his life has now returned to normal, he is engaged to be married, they’re going to buy a house,” he said.

“He was diagnosed as a child, so he had a restricted life up to that point, but now he is finding that normality in life.”

Mr Bowen said his nephew was on the deceased donor’s list, with no family member considered to be appropriate donors and urged everyone to consider opting in.

“He got a call because they got a perfect match for him and that’s why we keep talking about deceased donors, because if someone has unfortunately passed away they have a chance to leave a legacy to allow someone else to live a normal life,” he said.

He added live donors were becoming “increasingly common”, although restricted by the need to have two of something to donate.

“Live donors are a super special gift, it is becoming more prevalent too, through the media or their circle of friends, people see the advantages of being able to be a donor,” he said.

“There’s the closer bond and the benefit the recipient gets from it, and we’re not just talking kidneys here, there’s lots of other things that can help, such as bone marrow.”

Mr Bowen said Vikki had given him the greatest gift of all, though she was of the opinion she had benefited the most.

“I smile every time I think about it, I really do,” Mr Bowen said.

“My sister keeps reminding me she feels better from having donated than I do from having received it.”