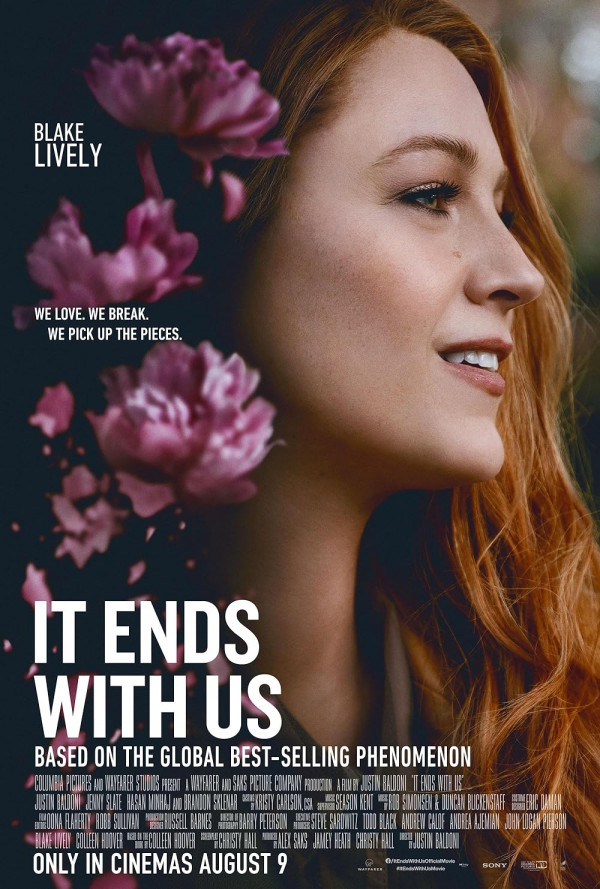

IT’S easy to be swept up in the flowery romance of It Ends With Us as Ryle Kincaid (Justin Baldoni) passionately pursues florist Lily Bloom (Blake Lively).

Lily tells the audience in the first scene that she is an unreliable narrator, but in the picturesque New England setting of Boston, Massachusetts, you join her in the illusion of Mr Right sweeping her off her feet.

As the film unfolds, Lily and the audience relearn what we already know: all is not what it seems, and the excuses ring false even in our own ears.

It Ends With Us is the beautiful, artfully directed portrayal of the domestic violence one in four Australian women will experience in their lifetime, taking the rose-coloured glasses off and realising a partner is unsafe, and making the choice to stay or go.

“It’s not something people talk about,” Lily says about witnessing her own mother’s experience with Lily’s dad while she grew up, voicing the ease with which domestic violence is kept behind closed doors.

The film utilises flashbacks to show her upbringing in a violent household and hold up the mirror to her present life with Ryle, which she swore would never mirror her mother’s.

(Kudos is due here to the casting directors for young Lily – yes, the mole matching Blake Lively’s is real and it’s unclear if the voice acting is dubbed.)

Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Sklenar) is the juxtaposition that shows what a fairytale romance looks like – from Ryle’s frustrated “Can’t you see what I’m trying to do here?” at Lily’s repeated rebuffs to his advances, to Atlas’s “If you ever feel ready to fall in love again, I’ll be here”, Lily’s autonomy and desires are centred.

Atlas reminds Lily of who she is and the strength she holds within herself to make the brave, scary choice – a choice that Lily learns was not an option for her mother.

Some critics have called It Ends With Us anti-feminist, but it is hard to agree when there is no such thing as a perfect victim and victim-survivors are conditioned to act within their abusers’ expectations.

It is hard to blame Lily when her conviction wavers, when coming to terms with one’s reality is hard, when abusers are skilled in saying the right thing at the right time to maintain power and control of the narrative.

It is hard to blame Ryle’s sister, Lily’s best friend and employee Allysa (Jenny Slate), when she tells Lily about Ryle’s own traumatic childhood story and says that as his sister she wishes Lily would forgive him, as to love is to forgive even when it seems impossible, but as a friend she sees that she could never expect her to continue.

What this film can be celebrated for is providing a nuanced depiction of a woman finding her strength, leaning on her supports and getting herself out of an abusive situation despite the perceived safety in choosing the alternative.

“What would you tell your daughter if she told you the person she loved was hurting her?” Lily asks Ryle

“What would you say to her?”

While this film is imperfect and the online commotion surrounding its promotion is unavoidable, Baldoni has translated a best-selling novel into a blockbuster that demonstrates the financial viability of complex narratives in cinema, and Lively’s Lily shows how a complex, strong, self-assured woman can find herself in this situation, and how she can get out of it.