By Huang Pei

When “listening” transcends its biological confines of the ear with perception unfolds toward broader dimensions of life, how can we dismantle the cognitive shackles of anthropocentrism and embraces a “living network of coexisting beings”? In Nanjing, China, a social experiment exploring animal ethics and disability inclusion is weaving long-overlooked channels of perception among animals, the hearing-impaired community, and the urban public — bridging the distance between city and countryside.

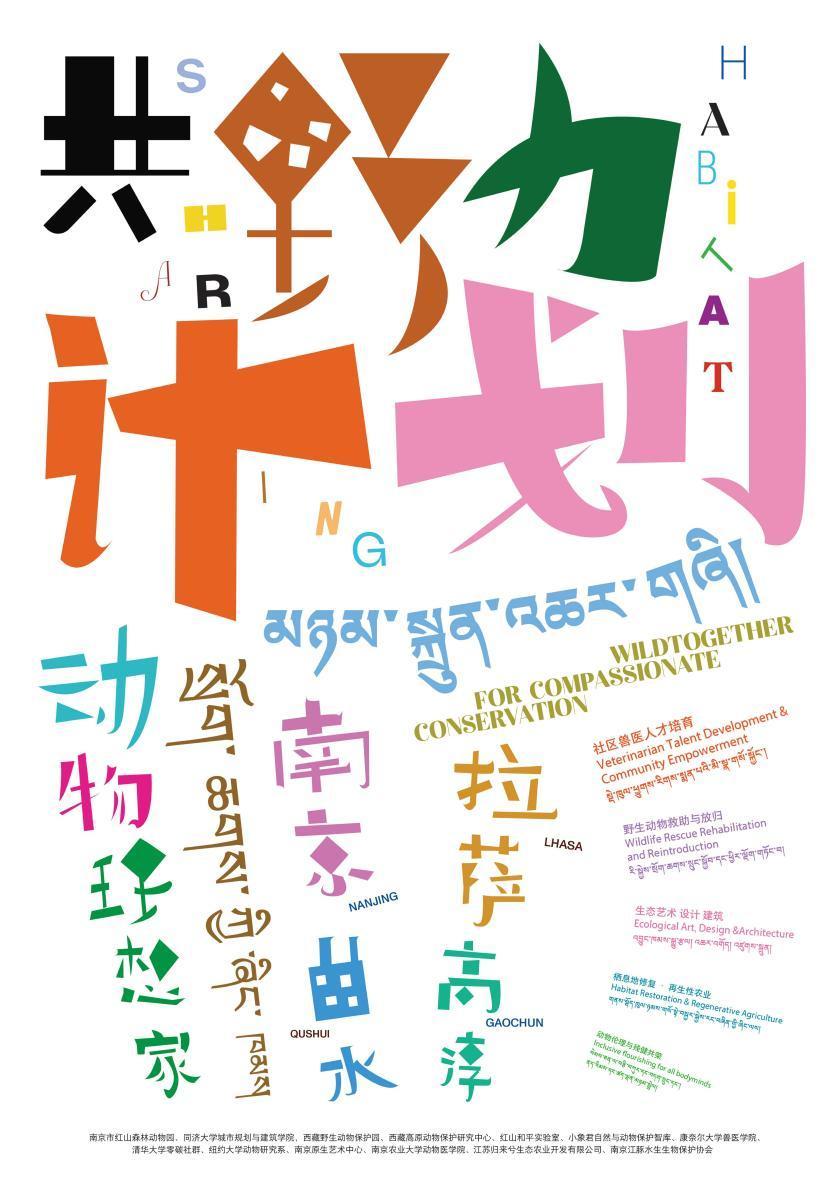

As a core initiative under the “Cohabitatat Initiative · WeWild Impact”, the Inter-Species Workshop gathers sound artists from both Argentina and China, partners of the hearing-impaired community, animal conservationists, and corporate participants. Together, they traverse urban zoos, rural farms, the bank along the Yangtze River, and city street corners, engaging in cross-sensory dialogues through field recordings, sound installations, and accessible guided tours.

Walking and listening thus become not only acts of reimagining the city but also a spiritual journey inward — an exploration of coexistence that begins with attention, empathy, and sound. The key breakthrough of this experiment lies in the deep inclusion of the hearing-impaired community. They are no longer “special participants” in an art event but active contributors who, through their unique sensory experiences, engage in a collective rewriting of humanity’s relationship with nature — reinterpreting what it means to listen and what it means to coexist.

On the opening night, the Nanjing Outsider Art Center transformed into an immersive sound laboratory. As the lights dimmed, Pan Xueyun, Co-founder of the Elefam Institute for Animal and Nature Conservation and curator of the workshop, began her talk with a moment of silence: “Rather than connecting animals and disability issues merely through ‘music’ or ‘sound,’ we see sound as a deeper medium — one that helps both hearing and hearing-impaired individuals t oawaken their senses and explore a shared, inclusive path where art converges with nature education.”

She observed that society has long constructed “valuable nature” through the able-bodied sensory norms, inadvertently obscuring the richness and complexity of ecosystems. This sensory privilege not only narrows human understanding of nature but also generates blind spots in environmental and animal protection. Dominated by visual and auditory experiences, mainstream perception prioritises visible crises such as plastic pollution or species extinction, while neglecting ecological processes that elude human senses — shifts in soil micro-organisms, noise-induced disruptions to animal navigation, or chemical dialogues among plants. Only by drawing insights from the perceptual modes of other life forms and embedding these perspectives into public awareness can humanity transcend its existing paradigms and cultivate a more reflexive and inclusive ecological consciousness.

Dawn at Hongshan: Tracing the Frequencies of Life in Red Mountain

At eight in the morning, Nanjing Hongshan Forest Zoo awakens through a veil of mist. Quietly, the soundscape experiment “Hongshan Podcast — Free Exploration” begins. Under the guidance of Licui, sign-language instructor from Nanjing School for the Deaf-mute, a group of hearing-impaired participants enter the wolf enclosure. They crouch to place recording devices, capturing the wolves’ low growls and social interactions, and lean close to air vents to attend to the faint flutter of wings and delicate taps of beaks. This may well be the first soundscape recording project in a Chinese urban zoo led by the hearing-impaired community. In these moment, nature’s whispers slip free from the dominance of sight and touch — and are, once again, truly “heard”.

As night descends upon Hongshan, washing away the day’s clamor, sound emerges as the sole compass. Led by Nature Interpreter Gao Yuan, small groups step into the darkness, tracing the chorus of insects, the cries of night birds, and the rustle of unseen creatures moving through the woods. Gao unravels the eco-logic behind each chirp and murmur, guiding participants to perceive the rhythm of life through vibration and frequency. In the absence of light, perception stretches, silence, becomes another way of listening. Within this ebb and flow of nature, they begin to feel a resonance— a pulse of life itself, a shared awareness flowing through every living things.

When these once-distant sounds are “seen” in the darkness, people are no longer passive “visitors” being fed information, but become active “hosts” who explore and perceive. These sounds seem to form a language that can be understood without hearing — vibrating through the body, creating a genuine dialogue between humans, animals, and nature. Li Ning, a hearing-impaired participant, reflected on the session: “The recording devices captured and amplified the subtlest sounds in the environment. Through the vivid descriptions of the sign-language interpreter, we could ‘hear’ the secret whispers of animals — the chirping of cicadas, the calls of François’ langurs, the songs of white-browed gibbons — each sound so wondrous, drawing us deeply into its world.”

When the hearing and hearing-impaired step into the same soundscape, listening transcends sensory boundaries and becomes an act of empathy. This echoes Hongshan’s longstanding conviction: a zoo transcends being a mere space for exhibiting animals, but an inclusive, multi-sensory world where every life tunes into its own frequency — and through mutual resonance, arrives at a gentler form of care for life.

Echoes of Yangtze River: The Dance of Finless Porpoises and its Rhythm of Breath

In the soundscape voyage “Dreaming with the River”, an immersive experience of listening, sensing, and coexisting unfolds along the gentle waves of the Yangtze River. By integrating sign-language interpretation and multi-sensory devices, the experience not only enables hearing-impaired participants “see sound” and “touch movement,” but also expand the very boundaries of ecological perception. What emerges is a truly shared public space — one rooted in inclusive coexistence, where, through collective sensory encounters, we draw closer to the finless porpoise and to one another.

Zhou Wei, from the Nanjing Yangtze Finless Porpoise Conservation Association, situates the fate of the porpoise within the narrative of local waterways, using imagery and video to illuminate the deep disruptions that human activity has imposed on the biodiversity of Yangtze River . Observer Pan Xingya, drawing from her field experience, leads both hearing and hearing-impaired participants into the porpoises’ natural habitat. There, by tracing breaths that rpple across the water and recording the rhythm of their surfacing, the group cultivcates a silent language of communication— one where gesture and body movement transcend auditory limits, becoming bridges of a deeper, shared understanding.

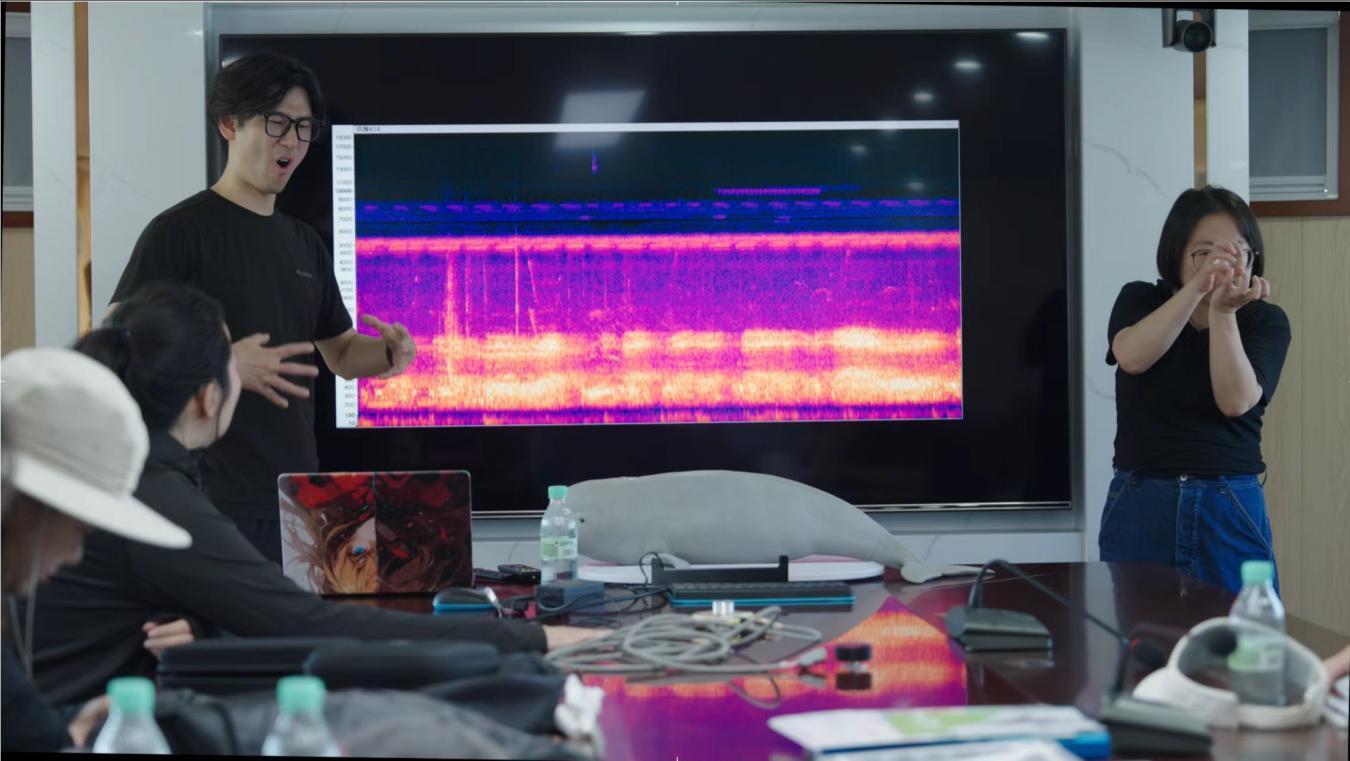

Sound artist Li Xingyu pushes these boundaries further in his work, “The Great Voyage of Sound.” From the deep hymns of Bryde’s whales to the polyphonic mrmurs of the Amazon rainforest, he repositions sound as a kind of shared vernacular —one that transcend geographies and biological differences. Through resonant speakers that render acoustic waves into tactile vibrations, he enables hearing-impaired participants to “listen through touch,” feeling the pulse of nature literally at their fingertips.

“ In the context of biodiversity acoustic monitoring, Li observes that “sound may bethe most egalitarian medium of communication, connecting the hearing and the hearing-impaired.” This meditation on sensory translation ignited deeper discussion and prompted a fundamental inquiry: What indeed, constitues the voice of nature? And in the absence of hearing, how do we reconstruct a bond with the living world? Ultimately , Li’s exploration asks how such embodied encounters can move us beyond reflection, toward sustained, everyday ecological stewwardship?

From the scientific narratives of porpoise conservation, to the sensory explorations of sound art, and the embodied practices of multi-sensory inclusion, participants did more than see the finless porpoise — they heard and felt the frequencies of nature itself. Amid the glimmers of the Yangtze River and the murmur of the wind, “accessibility” is no longer an abstract concept, but a tangible experience — one that invites every individual to step equally into nature’s story and to sense, with real weight, the interconnection of all living beings.

Traces of Beasts: Night Whispers of Nature among Stone Guardians

As dusk deepens, curator Wang Yanjun guides a group through the Great Golden Gate, across the Square City, and onto the Sacred Way of the Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum. Along this six-centuries-old imperial path, a procession of stone beasts — lions, xiezhi, camels, elephants, qilin, and horses stands in silent vigil. More than relics of a buried dynasty, they are coordinates in a civilisation’s imagination. When sight fades into darkenss, touch and hearing awaken–and through them, history begin to “speak.”

Argentine eco-musician Pablo Picco stands in quiet contemplation before these sculptures, tracing the cultural imprints behind these mythical creatures. In the contours of the qilin, he discerns divine lines that echo the ancient Maya and Aztec civilisations; in the proud stance of the xiezhi, he senses a universal ethos of justice transcending continents. As the stone figures shed their cold stillness, they become living conduits for a dialogue between nature and culture— Bagworm cocoons quivering in stone crevices, the low grunts of wild boars weaving with the faint glow of fireflies — nature, through its untamed language, begins to reinterpret the boundaries of human civilisation.

“These stone beasts crystallise humanity’s timeless yearning for ideal order,” Wang reflects as the procession moves through the twilight. “Where living creatures moving through its fabric, carved memories and natural acoustics merge into one inseparable resonance.” Along this nocturnal passage, the chisel strokes left by Ming artisans, the flutter of tree crickets, footsteps of modern wanderers, and the spiritual kinship between Eastern guardian beasts and Mesoamerican totems all converge into a seamless continuum— where temporal boundaries evaporate in darkness, and through sensory experience they reintertwined. History is no longer a specimen frozen in time, but as living organism that continues to breathe and evolve. By listening with attuned ears instead of analytical eyes, participants find in the murmur of the wind, the chorus of insects, and the rhythm of footsteps an unceasing conversation between civilisation and nature.

Voices of the Paddies : Tilling Together the Soil of Wisdom amid the croaking Frogs

At 4 a.m., in the pastoral silence of rural Nanjing’s Gaochun District, the Guilaixi Organic Farm awakens to the scent of fresh grass and the faint chorus of frogs. Workshop participants, stepping through the dew, enter the fields for the most vivid classroom of dawn. Farm director Zhou Jinbao begins with the story of bees and pollination, illustrating the delicate interdependence that binds the agricultural ecosystem together. Some participants crouch among the rice stalks to record the songs of insects; others translate sound waves into movement, improvising dances along the dikes — the voices of the earth crystallizing into a visible symphony of the land.

Here, life’s lessons are learned with our hands in the soil. Frogs, ladybugs, and hedgehogs are no longer distant “others,” but indispensable “neighbors in coexistence” within the farm’s ecosystem. The cyclical idea that “the field nurtures animals, and animals sustain the field” touches everyone present. As one participant wrote in her note, “Coexistence is not a concept — it’s a real conversation that happens every day along the ridges of the field.”

Yet behind this vitality lie systemic challenges facing organic agriculture. Committed to the principle of zero harm, the farm relies on eco-friendly measures such as insect-proof nets and biological pest control to respond to the “interference” of insects and birds — not through expulsion or killing. Zhou admits that high operating costs, low consumer enthusiasm, and the rise of misleading “pseudo-organic” products in the market have continually eroded public trust in genuine organic produce.

With the onset of early summer, a cattle egret is strolling and foraging in the fallow paddy field.

The path ahead remains steep, yet luminous with purpose. Gesturing toward the wetlands bordering the paddies, Zhou speaks with quiet conviction: “What we hold onto is more than a harvest–it’s a responsibility, a conscience. In partnership with Hongshan Forest Zoo, the farm is set to protect an endangered indicator species of farmland ecology — the Chinese immaculate treefrogs. Together, they aim to establish a new set of standards spanning the entire rice industry chain, from cultivation to consumption.

From building biodiversity-rich farmland systems to co-creating “Rice Field Theaters,” from promoting agro-ecological education to curating a Frog Chorus Arts Festival — each exploration seeks to bridge intangible ecological values and tangible cultural encounters. Here, every grain of rice tells a story of habitat restoration.

At Guilaixi Organic Farm, people plant more than rice — they are sowing the seeds of an everyday ecological civilisation. When society learns to perceive this deeper ecological value, agriculture rises beyond mere productive role and becomes an extension of culture, life and meaning itself. Such awareness lays a solid ground for renewing trust in organic farming–and in our shared future.

Nanjing Soundscapes: Where Encounters Resonate Beyond Boundaries

In his fluid “auditory diary,” Pablo reveals Nanjing as a living tapestry woven from resonant contrasts — wind breathing along the Ming City Wall, Yangtze finless porpoises murmuring in the waters, ceaseless traffic pulsing through Xinjiekou, and frog choruses rising from the paddies. These seemingly mundane sounds merge into an “acoustic map” of the city, charged with inner tensions and organic vitality.

Through ten days of attentive listening, Picco sensed a distinct sonic temperament that sets Nanjing apart from his Argentine hometown of Salsipuedes: here, urban density does not culminate in harshness, birdsong flows with poetic serenity, enveloping the city in a gentle, yet abundant auditory atmosphere. What touched him most, however, was his encounter with the local deaf community. Though unable to acess high-frequency sounds, they immerses themselves in live music through low-frequency vibrations and the rhythms of their own bodies. In that moment , it reshaped his understanding of music — no longer merely an art of hearing, but a holistic ritual of embodied perception, resonant beyond ear.

In one collective improvisation at the Outsider Art Center, hearing and hearing-impaired participants, along with sound artists, sat together in a circle, striking the ground and using their bodies as instruments. Deaf participants joined in by observing and mirroring the gestures of others, merging seamlessly into a “jungle chorus” without a conductor. In that moment, music rose above performance, becoming a profound act of “being together” — opening pathways of participation for the deaf while inviting the hearing to rediscover the boundaries of perception.

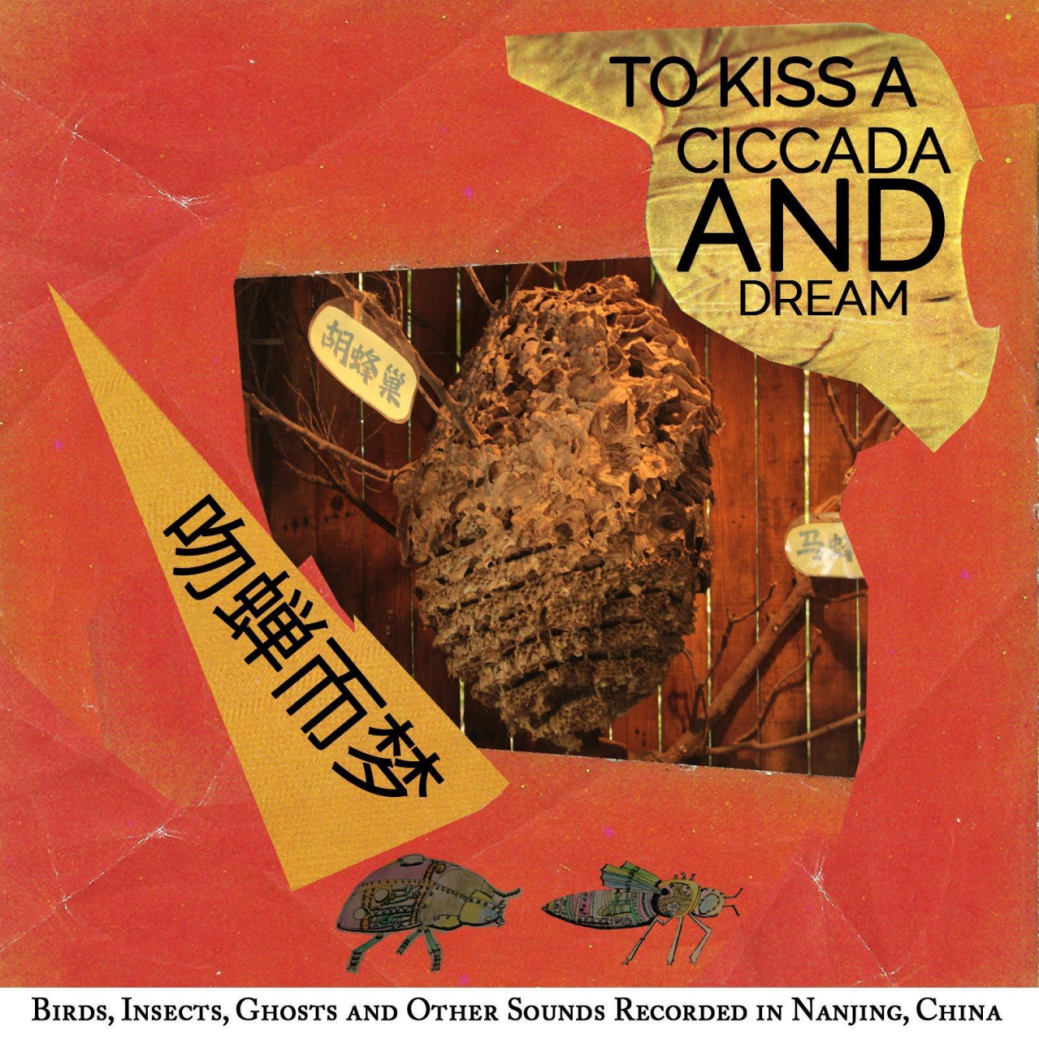

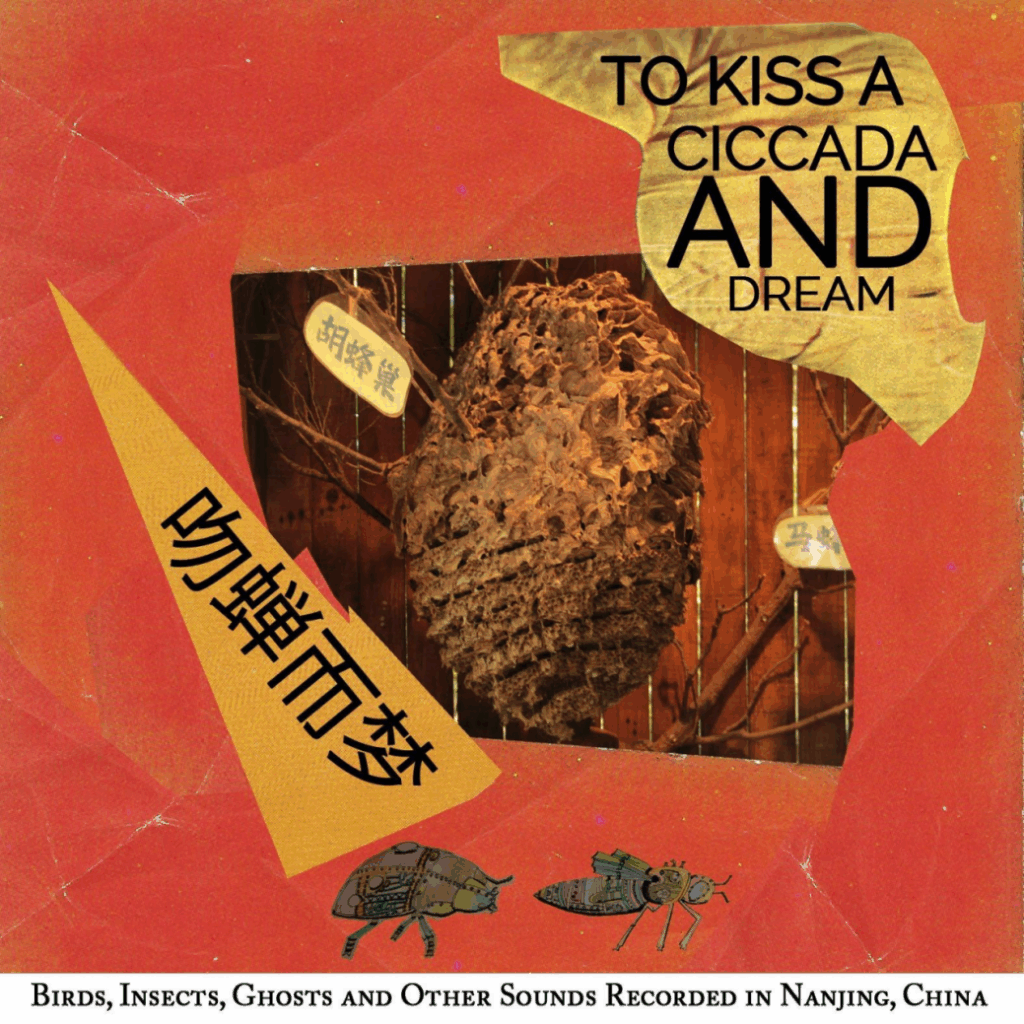

Picco’s album, To Kiss a Cicada and Dream (《吻蝉而梦》), blends storytelling, Chinese monologues, and ambient sounds, using stop-motion animation to give sound a visual form. “Nanjing’s soundscape — its diversity and inclusiveness — carries a healing power,” he reflected. “I hope to transform this experience into art — reminding every city dweller that even amid the noise, nature is always present.”

The Call of WeWildness: A Thousand-Mile Arc of Care from the Jiangnan to the Plateau

While Nanjing’s sound artists and the hearing-impaired community map the delicate interweaving of urban and natural soundscapes from dawn to dusk , a parallel narrative of guardianship — unfolds 3,600 meters above sea level at the Tibet Wildlife Conservancy. There, a different kind of care bridges not only East and West, but also perception and action, in a landscape where coexistence is both a practice and a philosophy.

As the only authorised wildlife rescue base in the autonomous region, the Conservancy echoes year-round with calls from the wild: tracking Himalayan black bears that stray into villages in the dead of night, or transporting injured snow leopards from the depths of snow-covered mountains. In just the first half of 2025, it successfully rescued 44 native animals, including snow leopards, Pallas’s cats, black-necked cranes, and white-lipped deer — bringing the total number of rescued animals to 597, most of which have since returned to the wild. Yet behind these remarkable efforts lies a structural challenge: outdated facilities and a shortage of trained professionals continue to constrain the long-term effectiveness of wildlife conservation on the plateau.

In Loma Town, Seni District, Nagqu City, veterinarian Zhaxi Deji and personnels from the local Forestry and Grassland Bureau examine an injured black-necked crane.

In August, the Conservancy became a gathering ground of “cohabitat visionaries” —— Tibetan and Han scholars from Tongji University, Tsinghua University, Fudan University, the University of Oxford, University College London, and SOAS University of London, joined by veterinarians, keepers, herders, cultural curators, and government practitioners working on the frontlines. They were not detached observers, but WeWilders— engaged activists navigating complex ecological and social realities through embodied action, toward a future of multispecies care and transcultural coexistence. Together, they investigate the salt-licking ritual of wild yaks, the cyclic migration patterns of Tibetan wild asses, and the mixed-species grouping between white-lipped deer and other species, they reinterpreted the herbivore grazing zones as dynamic lifeworlds. In the process, they seek to regenerate the plateau’s own rhythms and breath into organic design language — one rooted in, and resonant with, the land itself.

Originating from Hongshan Forest Zoo in Nanjing, traveling to Qushui in Lhasa, and returning to the rural wetlands and paddies of the middle and lower Yangtze — Gaochun, the “Cohabitatat Initiative · WeWild Impact” traces a meaningful geographical arc of conservation that stretches from urban environmental awareness to the plateau on-the-ground efforts.

Grounded in socially engaged eco-art and design practices, the initiative is rooted in improving wildlife rehabilitation and reintroduction, cross-regional training of veterinary professionals, animal ethics and disability inclusion, as well as habitat restoration and regenerative agriculture. It strives to weave a “community of care for all life” — one that interconnects multiple species, communities, and regions. This endeavor not only expands and redefines the notion of “protection,” but also gently yet resolutely restores the ruptured channels of perception and the neglected ethical bond with nature.

With the joint establishment of the Plateau Wildlife Conservation Research Center by the Tibet Wildlife Conservancy in Lhasa, Nanjing Hongshan Forest Zoo, and Tongji University, a new form of collaboration is emerging — transcending geographic boundaries and industry barriers. It is no longer confined to “point interventions” centered on technical rescue; instead, it shifts toward “systemic collaboration” that integrates community capacity-building with multispecies care. What was once relatively isolated “local practice,” both geographically and cognitively, is gradually evolving into a multi-centered, cross-regional approach to talent development and institutional co-creation. This boundary-breaking attempt in ecological conservation aims to cultivate a “WeWild space” that can stimulate people’s bodily perception and willingness to act. Here, individuals can tangibly experience the deep-rooted spiritual connections between the plateau’s ecology and Han-Tibetan cultural traditions, embedded in the very fabric of the land and its belief systems.

Against the backdrop of escalating global habitat fragmentation and deepening geopolitical divides, the “WeWild Impact” confronts a critical rapture at the heart of modern civilisation: the disconnection between the politics, economy, cultural systems and the imperative for ecological conservation. It champions a development ethic built on the “coexistence of all beings, co-flourishing of regions, and co-sharing of civilisational heritage.” At its core, the initiative challenges the objectification of nature as a mere resource to be gazed upon or consumed, seeking instead to reembed human societies within the integral and interdependent narratives of ecological and cultural networks. The vision takes tangible form through the joint efforts of Han and Tibetan communities in a “community of care for all life” — where conservation is no longer confined to a patchwork of techno-solutionism, but represents an attitude of civilisation— a conscious reweaving of the web of life rooted in reverence and reciprocity.

As the initiator, the executive director of the Tibet Wildlife Conservancy and a practice-based scholar at University College London’s Institute for Global Prosperity, Huang Pei puts it: “What we are trying to break are the invisible walls that stand between nature and culture, the able-bodied and the disabled, conservation and development. What we are calling for is a reconstruction of spatial order and life narratives — transcending anthropocentric geographic divisions to build a ‘community of care for all life,’ rewoven through shared habitats, intertwined life trajectories, and uncertain yet hopeful futures. Here, snow leopards, birds in flight, people with disabilities, herders, and even the wind in our ears, the memory-laden land — all shed the label of ‘the other’ to become ‘co-inhabitants’ who perceive one another and tell their stories together.”

From the sonic art interventions in Nanjing to the ecological design explorations in Lhasa, art and design have transcended their traditonal roles as creators of form and space. They now function as mediators—reweaving relational fabrics of life — connecting “habitat to city” while bridging “culture and ecology.” This shift propels conservation from isolated “islands” toward a socio-ecolgical networks, extending restoration from shaping the built environment to the co-creation of shared culture and psychology. Conservation, therefore, is no longer a solitary guardianship or one-way intervention, rather a benificiary circle where it is interwoven with development, each being both the cause and effect. What emerges is a response not only to the technical question of saving endangered species, but to a deeper and even fundamental inquiry: on this land of multi-ethnic coexistence and multispecies cohabitation, how might we, with empathy and collaborative wisdom, construct an alternative future that is more inclusive resilient for all forms of life?

The “WeWild Impact” transcends mere protective sentiment or empathetic impulse, embodying instead a form of proactive activism dedicated to “breaking walls” — forging bridges of understanding and connection across divides — between different social groups, cognitive frameworks, civilisational paradigms, and even across species. As Huang elaborates, “ intergenerational experiences, urban-rural insights, Han and Tibetan cultures, and even the perceptual wisdom of other living beings together form an irreplaceable, pluralistic knowledge system. Our endeavor is to translate such a reservoir of survival wisdom into lasting nourishment for the sustained evolution of regional civilisations. Anchored in integrated ecological and cultural values, it seeks to interweave participatory conservation education, community-benefit economies, and sustainable livelihoods into a cohesive process that reciprocally shape both spatial planning and development ethics.”

Now launching on the plateau, the “Cohabitatat Initiative · WeWild Impact” brings together collaborators across policy, business, culture, academia, media, and local communities. Together, they aim to co-create an ecological restoration corridor and a talent cultivation network that connect the city (Hongshan) with the plateau. As a key vehicle of this vision, the Conservancy will be transformed into a gateway for public encounter with plateau wildlife — a scene evoking empathy for life, a hub for cross-sector collaboration, and a testing ground for exploring new economic models. Ultimately, it aspires to become a spiritual home where Han and Tibetan cultures converge, learn and grow together.

The actualisation of these considerations depends on a functional platform for civic engagement — one that mediates between government and community interests, harmonises commercial objectives with the generation of social value, and ultimately matures into a polycentric collaborative governance model. Through this, a paradigm shift in perspective becomes possible: environmental stewardship ceases to be perceived as the costs and sacrifices of development, but rather is reimagined as the infrastructure for urban functioning, a new logic for business innovation, and a deep wellspring of wisdom for dwelling.

Tibetan herders staged “The Dance of Jiuhe river” with waist drums against the backdrop of sand dunes at the Plateau Dune Art Festival in ShannanWhile sustaining eco-cultural health, fostering intercultural understanding, and strengthening community bonds grounded in “coexistence for mutual benefit” may not yield immediate returns, they are far-sighted investments in the evolution toward a higher form of civilisation. This marks not only the beginning of a new trajectory of growth, but also the foundation upon which future generations will build their existence.

When the breath of the snow-covered plateau converges with the pulse of the Jiangnan wetlands along a single thread of development, the demands of economic growth and the imperatives of ecological survival are weighed on the same scale. The “firework tragedies” in the Himalayas epitomises a local microcosm of “development anxiety”–the relentless pursuit of short-term gains is imposing an unaffordable weight upon the cause of long-term conservation. The “WeWild Impact” responds to this profound question of our time: how can the ambitions of urban development leave room for the authentic perception of countless lives? Amid the tension between fast-paced progress and slow living, foresight and immediate concerns, construction and habitation, can we find the crucial fulcrum that sustains balance?

Perhaps it starts with a reset of perception: learning to “feel and hear” the wingbeats of “chongchong”(ཁྲུང་ཁྲུང), the black-necked cranes soaring above the Burhalah Palace, to “read” the silence of the stone beasts guarding Ming Xiaoling Mausoleum in the depth of night, and to let the rain frogs sing for the fertile, rippling rice paddies of Gaochun. Only through such direct encounters can one truly understand that what the “WeWild Impact” seeks to restore is the spiritual bond between humanity and nature — a thread nearly severed by modernity.

Thus, when the flyways of migratory birds begin to intersect with the trajectories of urban development upon a shared blueprint, and when ecological values are woeven into the very narrative of our development ethos, the measure of civilisation has been recalibrated accordingly. It is no longer gauged solely by economic growth metrics, but points instead to the depth and breadth of lived experience–its richness, diversity and its inclusiveness. What we create at this moment is more than an ecological corridor for sustaining wildlife, but a symbiotic wisdom for navigating complex realities — one that transcends binary oppositions, and rigid either-or dilimmas. It seeks a dynamic balance within perpetual tension — embracing the impulse for growth while honoring the instinct to dwell; responding to the call of the times while listening to the murmurs of the earth. Perhaps this is how we begin to relearn in this clamorous age what it means to truely inhabit the land.