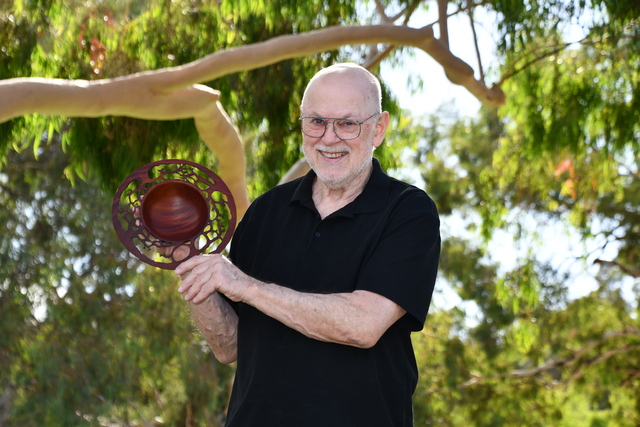

FOR decades, Brian Gibson has helped protect every community he has worked and lived in.

But last month, the former Victoria Police sergeant was forced to protect himself, handing in his badge after 29 years with the force.

Mr Gibson was forced to ill-health retire from the Kerang Police Station on September 29 because of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He moved to Kerang in 2004 after being promoted to the rank of sergeant.

“In 1989, I made the bold move to join Victoria Police. I had the vision of a long and fruitful career serving the people and the state of Victoria, back then we even served the Queen,” he said.

“Over the coming years, I made the most of many opportunities to develop my skill set and not once did I ever take a backward step, as with all first responders, we ran at danger and not away from it.”

“Over the coming years, I made the most of many opportunities to develop my skill set and not once did I ever take a backward step, as with all first responders, we ran at danger and not away from it.”

Mr Gibson said the one challenge he was not able to overcome was the Kerang rail disaster, which ultimately ended his career, ironically on Police Remembrance Day.

“In 2007 life changed for not only myself but also for my family and the community as a whole. You see on June 5, 2007, at around 1342 hours, I, along with two senior constables, was the first supervisor to the worst rail disaster that this state had seen for more than 30 years,” he said.

A truck hit a Bendigo-bound V/Line passenger train at a level crossing on the Murray Valley Highway, north of Kerang, killing 11 people.

“This incident changed me forever and caused a workplace injury that I battled with for nearly nine years before finally succumbing to the injury,” Mr Gibson said.

“I put my family, and community, ahead of my own wellbeing, as many members do, and continued to work. I attended further incidents but this one has always remained with me and I have battled hard to perform my role, even trying for promotion for a couple of years.”

Mr Gibson’s wife, Katrina, told The Guardian last year, to mark the 10th anniversary of the disaster, she lost the man she fell in love with, “her husband and father to our four children”.

“I had no idea how much a major incident could have a flow on effect and affect people that the only connection to the accident, was being a family member or friend that was not at the scene,” she said.

“Even though he did not die that day, he came home, or at least his body came home.

“He walked in the door later that night exhausted, a ghost of a man.

“Little did I know my man was gone and that reality would take me years to finally realise and accept.”

Mr Gibson said there was no fanfare and no ticker tape parade on his final say, “just the clock ending a career way too early”.

Mr Gibson applauded Chief Commissioner Graham Ashton for “taking the time and effort to walk to support mental health”, but argued there was “so much more that needs to be done to make it better into the future for our younger members to feel that they will be supported and not just thrown on the scrap heap when diagnosed with PTSD”.

“We can all sit around talking about how we value our members and that the organisation is working on ways to make it better, I can advise you that although you may believe this and the media are reporting it, there are way too many managers who are ignorant to the fact that PTSD is real and is extremely damaging.”

Mr Gibson joined the chief commissioner on Monday, along with wife Katrina and son Logan, for 12km through the Murray Mountain Rail Trail near Myrtleford as part of the Head to Head fundraising walk.